Few Markham residents thought they’d ever see an act as twisted and terrifying as Jennifer Pan’s again.

Instead, they witnessed one far more evil.

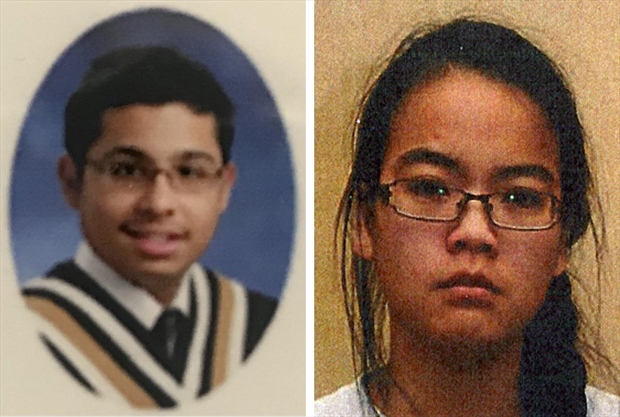

It was in 2010 when Pan’s Hollywood-style murder-for-hire plot — to kill her immigrant parents all the while acting like a victim during a home invasion/robbery — came to fruition.

Her mother, Bich-Ha, was murdered by a group of thugs.

Her father, Hann, miraculously survived.

Jennifer, her ex-boyfriend and their cohorts were jailed for life in 2017.

Almost a decade later, tragedy struck again, this time even more gruesome — a quadruple homicide with arresting similarities.

In 2019, a Markham video-gaming recluse named Menhaz Zaman, 23, just a year younger than Jennifer at the time of the Pan incident, murdered his mother, grandmother, sister and father with a crowbar, followed by a knife across their throats.

It left many wondering how lightning could strike twice in the same community of fewer than 400,000 people.

“It’s amazing that it happened twice in one city … it’s really quite remarkable,” said Dr. Jaswant Guzder, a psychiatry professor at McGill University. “It’s a horrific crime, that’s highly unusual.”

In the Pan case, Jennifer was the eldest child and under plenty of pressure to achieve immense success at her scholarly pursuits, as well as her pastimes, such as figure skating and piano.

Her parents all but insisted she attended Ryerson for pharmacology.

Problem was it was all a masquerade — showing parents fake report cards, buying textbooks and sitting around the library all day, but not actually attending school.

When they finally figured out she’d been lying, Jennifer was locked in the house and spent almost a year in her room plotting their murder.

Menhaz’s parents both thought he was attending York University and taking mechanical engineering.

In reality, he was catching the bus each day, wandering the campus or heading to Markville Mall to keep up the ruse.

In the lead up to the day he was supposed to graduate, July 28, 2019, he followed through on his murder plan, which was three years in the making.

While Pan continues to maintain her innocence, Menhaz pleaded guilty on Sept. 24.

Dr. Hiram Mok, a psychiatrist focusing on mood disorders and cross-cultural psychiatry, believes the problems in both cases are relatively common inside immigrant homes from these regions – Vietnam and Bangladesh – but admitted this outcome is very rare.

Often problems like these can manifest inside the homes of immigrant families when parents move to more prosperous countries and work menial jobs, he said, putting their own careers on hold.

We know that Jennifer’s father, a tool and die maker, worked extremely hard at Magna and refused to take vacations in order to save cash until his children graduated.

Menhaz’s father was a taxi driver, an occupation where the drivers are often overworked and overqualified immigrants.

“Parents project their own immigrant expectations onto their kids,” Dr. Mok said. “They can put pressure on the kids to achieve their unfulfilled dreams … the immigrant dream.”

This sort of pressure can result in children leading double lives so as not to disappoint the parents, while maintaining their own freedoms, he said.

“This can lead to deception and fantasy, because (the children) don’t have a life, no friends, no dating, no sex; it’s very strict, almost like a religion,” he said.

He told a story of a female he knows of, who would receiving 97 per cent on exams only to be directed by her mother to demand of the teacher why she was missing the final 3 per cent.

Dr. Soma Ganesan, a psychiatrist and founder of Vancouver General Hospital’s cross culture clinic, said cultures around the globe rank professions in terms of prestige, with doctors, engineers and lawyers at the very top.

Dr. Ganesan noted that in certain parts of the world, there is a sort of social contract between parents and children.

“(The deal is) I will work hard, 12 hours a day, I will take no vacation and I will do this to provide a warm and comfortable house for you,” he said. “(But then the) children are under tremendous pressure to enter university and a prestigious program.”

Born in Vietnam to an Indian father, Dr. Ganesan further explained how feelings of resentment and desperation can fester inside children, who often have little opportunity to voice their own opinions.

“Parents express their love by providing safety to grow and opportunity to educate, but they have expectations of the children to do well in school,” he said.

He told the story of a young man he knows of who lied about attending university only to end up disappearing from his family’s life altogether, rather than lose face and admit the deceptive behaviour.

Dr. Mok added that while this sort of pressure can result in educational and career successes, it can also leave the individuals in misery during adulthood.

“Some become high achieving in life, but they are never happy; they have an empty feeling inside,” he said. “The feeling may sound like, ‘I don’t know who I am.’ They can lead normal lives, but only with psychological attention.”

For many, the most shocking part of the murders may be both Jennifer’s and Menhaz’s desperate plotting and planning, without either finding another way out of the predicament.

Prior to his arrest, Menhaz wrote the following on a chat app: “I wanted them to die so that they didn’t suffer knowing how much of a pathetic subhuman I was.”

Dr. Ganesan believes issues can involve saving face for the individual or the family.

“They were born in Canada, in a mixed culture, where they see freedom of speech at school and hierarchical rigidity when they get home,” he said, speaking in general terms and not about individual cases. “There’s post-traumatic stress, pressure in the family, social isolation, verbal abuse; they feel continuously sad and depressed for a long time. There are serious symptoms of depression … they can lack the ability to control the mind. Without intervention, the final stages of depression is homicidal or suicidal.”

Dr. Guzder, head of child psychiatry at Montreal’s Jewish General Hospital, believes what can help immigrants so much when they come to Canada, their collectivist ideals, can also result in tragic situations like these ones.

She said Western cultures stress autonomy, preparing children to leave the nest and move on to live alone and possibly start their own families.

That mentality stands in contrast to Asian cultures that are based on familial support, where small communities help one another to an extraordinary degree.

“There’s a strain between these two polarities,” she said. “Adolescents in the dominant culture have to navigate what’s positive and negative of both those cultures.”