With permanent residence visas in hand, they sold their houses, quit their jobs and even shipped some of their belongings to their new homes in Canada.

Then hit, closing international borders and leaving them high and dry — without a home, job or path to restoring their stalled immigration dreams.

While the federal government is striving to restart an immigration system halted by the coronavirus pandemic and to make up for its 2020 shortfall, tens of thousands of would-be newcomers who have the visas to settle here permanently are being kept outside Canada. Some of their visas have now expired.

It’s a situation that has left many hurt, frustrated and worried for their future.

The teacher and the massage therapist

Belarussian Fatima Camara and her husband quit their jobs, sold their home and pulled their five kids out of school after they got their confirmation of permanent residence and visas stamped on their passports in late March.

They found a realtor and rented a place where they could quarantine for a month in Dieppe, N.B. They sent their bikes, shoes and clothes in aniticipation of the life-changing move from Minsk.

Today, they have no idea where those shipments went, because they weren’t there to pick them up.

“We stay in Belarus without a home, jobs and are absolutely hopeless,” said the French and English teacher and part-time massage therapist, whose family’s permanent residence visa is expiring in December.

“Our immigration plan and our lives are ruined.”

Since mid-March, Ottawa has imposed strict travel restrictions against foreign nationals, including holders of permanent resident visas who have yet to be admitted into the country. It had planned to welcome 340,000 newcomers this year, a target that’s expected to fall short by 40 per cent.

Currently, Canada only allows entry to those who have a permanent resident visa issued before March 18 to settle here permanently. A border officer will still ask questions about their reasons for coming now and ensure self-isolation rules are being respected.

Those with their visas stamped after that date, such as Camara, need to apply for an authorization to travel before they can board a flight, unless they are living in and coming from the United States.

Would-be immigrants with expired visas are asked not to contact the immigration department until they are ready to travel. Only in July, did officials introduce a webform for expired visa-holders to apply for an authorization letter and be assessed by a list of criteria, including whether they have compelling reason to travel to Canada now.

According to an immigration department spokesperson, 15,786 applicants who received their visas before March 19 have had their documents expire as of the end of October. About 2,700 principal applicants filled out the webform and more than 120 received authorization.

The accountant

Prashant Gupta of India received his visa in January and had booked a flight for March 18 before postponing the trip. Since then, he twice tried unsuccessfully to board a flight in May to get here before his visa expired in June, despite Ottawa’s policy to exempt those who got their visa before that date. (Both Canada-bound flights were repatriation flights, restricted to Canadian citizens and already landed permanent residents.)

After months of waiting, the chartered accountant from Kolkata was thrilled to get an authorization letter from the Canadian government on Nov. 6. But he was again refused boarding, this time because Air India would not recognize the expired visa, despite the authorization document.

“I was offloaded at the last moment and not allowed to enter the aircraft. I have asked the Canadian embassy for help, but have yet to receive a response. There was another girl who suffered the same fate,” noted Gupta, who had a job offer in Toronto for a position in financial acquisition that’s no longer valid since he couldn’t make it to Canada.

“This has really broken me. The economy is bad. I can’t go back to my previous job. I have no income. My life has just stopped and stalled.”

The nurse

Registered nurse Katie Hilton, who had previously worked in British Columbia for two years, said she and her husband, Rich, a broadcast journalist, invested three years of their life and more than $10,000 in the immigration process.

They went through and paid for the required English language test, medicals, police clearance, education credential assessement and her licensing registration before she, as the principal applicant, was selected by the Alberta government in 2019 through a provincial immigration stream based on her skills.

Hilton already has a job lined up as part of a new COVID-19 service for the Indigenous community just north of Cochrane, but she needs to arrive and complete her quarantine before the end of November.

“While I completely understand the borders being closed to the vast majority of people at the moment, I can’t understand why those in essential roles aren’t being fast-tracked, especially over the autumn and winter period, when we know there will be a surge in COVID cases,” said Hilton, who received her visa in late October.

She became even more frustrated this week when she was issued the authorization letter, but told her 10-year-old son, Benjamin, does not meet the exemption requirement.

“I’m honestly speechless at how ridiculous these rules are. What kind of government separates a mother and child?” asked Hilton.

“I’m now having to choose between either using the exemption letter but leaving my child in the U.K, having to rely on my elderly parents to help with child care and potentially exposing them to the virus for which I’d never forgive myself … or stay in the U.K. to be with my child and lose my job.”

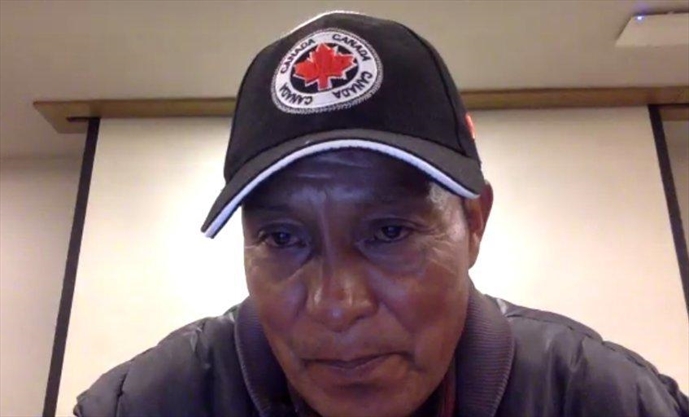

The cyber security worker

Fadi Ghaoui, who quit his job in cyber security in Saudi Arabia and moved back to Lebanon in April for the move to Canada, said many would-be newcomers have had their lives put on hold and it has taken a heavy financial toll on them. After they quit their jobs, they must now dip into the settlement fund they’d set aside.

“I have used 30 per cent of my savings intended for our new life in Canada just to survive in Lebanon,” said Ghaoui, who received his family’s permanent resident visas on Jan. 7 and had booked their flight for May, two weeks before the visas expired on June 6. They couldn’t leave because his country was in lockdown.

At the end of June, he got an email from the Canadian visa post in London that his permanent residence application was under review to see if anything would need to be updated, such as a new medical clearance before another visa would be issued.

His family was among the survivors of the Aug. 4 explosion that levelled the Beirut port, killing more than 200 people and injuring 6,500. They were three kilometres away, witnessing the flattening of the site when it happened.

Despite the Canadian government’s special program to speed up immigration applications for blast victims in the area, the family has yet to hear an update to their application.

“I do not have a house anymore. I do not have a job anymore. There is no security in my country. The economic situation is bad. We feel so insecure. I fear for our future,” said Ghaoui, who, along with his wife and daughter, is staying with his parents.

“We are barely surviving here. We are stuck. Should we rent a house? Should we unpack all our bags again? Leave for the Gulf? Or just wait for Canada immigration’s response? Being in limbo is the worst.”

Nicholas Keung is a Toronto-based reporter covering immigration for the Star. Follow him on Twitter: